Airplane ear

![]() August, 10th, 2023

August, 10th, 2023

Benefit Summary

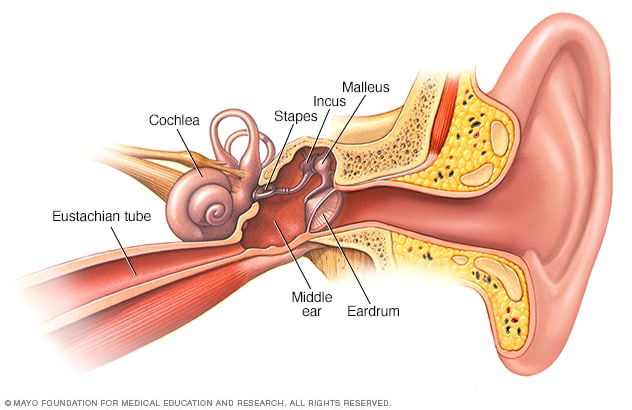

That fullness in your ear when on an airplane that’s climbing or descending results from uneven air pressure between your middle ear and the environment.

Overview

, Overview, ,

Airplane ear (ear barotrauma) is the stress on your eardrum that occurs when the air pressure in your middle ear and the air pressure in the environment are out of balance. You might get airplane ear when on an airplane that’s climbing after takeoff or descending for landing.

Airplane ear is also called ear barotrauma, barotitis media or aerotitis media.

Self-care steps — such as yawning, swallowing or chewing gum — usually can counter the differences in air pressure and improve airplane ear symptoms. However, for a severe case of airplane ear, you might need to see a doctor.

Symptoms

Airplane ear can occur in one or both ears. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Moderate discomfort or pain in your ear

- Feeling of fullness or stuffiness in your ear

- Muffled hearing or slight to moderate hearing loss

If airplane ear is severe, you might have:

- Severe pain

- Increased ear pressure

- Moderate to severe hearing loss

- Ringing in your ear (tinnitus)

- Spinning sensation (vertigo)

- Bleeding from your ear

When to see a doctor

If discomfort, fullness or muffled hearing lasts more than a few days, or if you have severe signs or symptoms, call your doctor.

Causes

Airplane ear occurs when the air pressure in the middle ear and the air pressure in the environment don’t match, preventing your eardrum (tympanic membrane) from vibrating normally. A narrow passage called the eustachian tube, which is connected to the middle ear, regulates air pressure.

When an airplane climbs or descends, the air pressure changes rapidly. The eustachian tube often can’t react fast enough, which causes the symptoms of airplane ear. Swallowing or yawning opens the eustachian tube and allows the middle ear to get more air, equalizing the air pressure.

Ear barotrauma can also be caused by:

- Scuba diving

- Hyperbaric oxygen chambers

- Explosions nearby, such as in a war zone

You may also experience a minor case of barotrauma while riding an elevator in a tall building or driving in the mountains.

Any condition that blocks the eustachian tube or limits its function can increase the risk of airplane ear. Common risk factors include:

- A small eustachian tube, especially in infants and toddlers

- The common cold

- Sinus infection

- Hay fever (allergic rhinitis)

- Middle ear infection (otitis media)

- Sleeping on an airplane during ascent and descent because you aren’t actively doing things to equalize pressure in your ears such as yawning or swallowing

Complications

Airplane ear usually isn’t serious and responds to self-care. Long-term complications can rarely occur when the condition is serious or prolonged or if there’s damage to middle or inner ear structures.

Rare complications may include:

- Permanent hearing loss

- Ongoing (chronic) tinnitus

Prevention

Follow these tips to avoid airplane ear:

- Yawn and swallow during ascent and descent. These activate the muscles that open your eustachian tubes. You can suck on candy or chew gum to help you swallow.

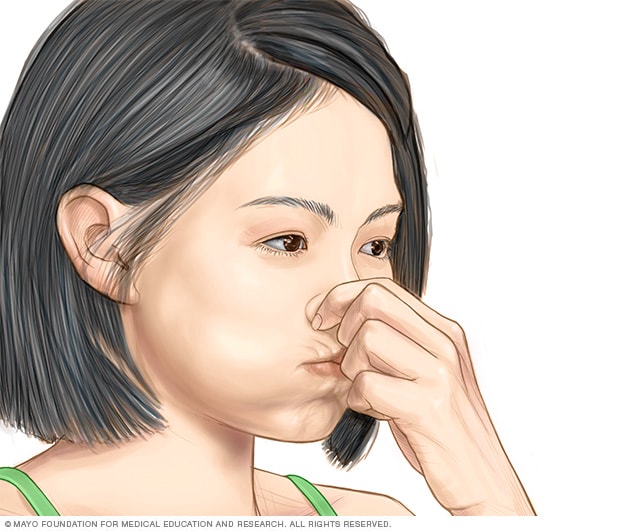

- Use the Valsalva maneuver during ascent and descent. Gently blow, as if blowing your nose, while pinching your nostrils and keeping your mouth closed. Repeat several times, especially during descent, to equalize the pressure between your ears and the airplane cabin.

- Don’t sleep during takeoffs and landings. If you’re awake during ascents and descents, you can do the necessary self-care techniques when you feel pressure in your ears.

- Reconsider travel plans. If possible, don’t fly when you have a cold, a sinus infection, nasal congestion or an ear infection. If you’ve recently had ear surgery, talk to your doctor about when it’s safe to travel.

- Use an over-the-counter nasal spray. If you have nasal congestion, use a nasal spray about 30 minutes to an hour before takeoff and landing. Avoid overuse, however, because nasal sprays taken over three to four days can increase congestion.

- Use decongestant pills cautiously. Decongestants taken by mouth might help if taken 30 minutes to an hour before an airplane flight. However, if you have heart disease, a heart rhythm disorder or high blood pressure or you’re pregnant, avoid taking an oral decongestant.

- Take allergy medication. If you have allergies, take your medication about an hour before your flight.

- Try filtered earplugs. These earplugs slowly equalize the pressure against your eardrum during ascents and descents. You can purchase these at drugstores, airport gift shops or a hearing clinic. However, you’ll still need to yawn and swallow to relieve pressure.

If you’re prone to severe airplane ear and must fly often or if you’re having hyperbaric oxygen therapy to heal wounds, your doctor might surgically place tubes in your eardrums to aid fluid drainage, ventilate your middle ear, and equalize the pressure between your outer ear and middle ear.

Helping children prevent airplane ear

To help young children:

- Encourage swallowing. Give a baby or toddler a bottle to suck on during ascents and descents to encourage frequent swallowing. A pacifier also might help. Have the child sit up while drinking. Children older than 4 can try chewing gum, drinking through a straw or blowing bubbles through a straw.

- Avoid decongestants. Decongestants aren’t recommended for young children.

Your doctor will likely be able to make a diagnosis based on your history and an examination of your ear with a lighted instrument (otoscope).

Treatment

For most people, airplane ear usually heals with time. When the symptoms persist, you may need treatments to equalize pressure and relieve symptoms.

Medications

Your doctor might suggest you take:

- Decongestant nasal sprays

- Oral decongestants

To ease discomfort, you can take a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve), or an analgesic pain reliever, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others).

Self-care therapies

With your drug treatment, your doctor will instruct you to use the Valsalva maneuver. To do this, you pinch your nostrils shut, close your mouth and gently force air into the back of your nose, as if you were blowing your nose.

Surgery

Surgical treatment of airplane ear is rarely necessary. Even severe injuries, such as a ruptured eardrum or ruptured membranes of the inner ear, usually heal on their own.

However, in rare cases, an office procedure or surgery might be needed. This might include a procedure in which an incision is made in your eardrum (myringotomy) to equalize air pressure and drain fluids.

Preparing for your appointment

If you have severe pain or symptoms associated with airplane ear that don’t improve with self-care techniques, talk to your family doctor or a general practitioner. You might then be referred to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist.

What you can do

To prepare for your appointment, make a list of:

- Your symptoms and when they began

- All medications, vitamins or other supplements you take, including doses

- Questions to ask your doctor

Questions for your doctor about airplane ear might include:

- Is my ear discomfort likely related to my recent airplane travel?

- What is the best treatment?

- Am I likely to have long-term complications?

- How can I prevent this from happening again?

- Should I consider canceling travel plans?

Don’t hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Your doctor will ask you questions, including:

- How severe are your symptoms?

- Do you have allergies?

- Have you had a cold, sinus infection or ear infection recently?

- Have you had airplane ear before?

- Were your past experiences with airplane ear prolonged or severe?

What you can do in the meantime

To treat pain, you might take a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve), or a pain reliever, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others).