Huntington's disease

![]() May, 21st, 2024

May, 21st, 2024

Benefit Summary

This rare disease causes an early decay of nerve cells in the brain. Learn about its symptoms and how treatments may help.

Overview

, Overview, ,

Huntington’s disease causes nerve cells in the brain to decay over time. The disease affects a person’s movements, thinking ability and mental health.

Huntington’s disease is rare. It’s often passed down through a changed gene from a parent.

Huntington’s disease symptoms can develop at any time, but they often begin when people are in their 30s or 40s. If the disease develops before age 20, it’s called juvenile Huntington’s disease. When Huntington’s develops early, symptoms can be different and the disease may have a faster progression.

Medicines are available to help manage the symptoms of Huntington’s disease. However, treatments can’t prevent the physical, mental and behavioral decline caused by the disease.

Symptoms

Huntington’s disease usually causes movement disorders. It also causes mental health conditions and trouble with thinking and planning. These conditions can cause a wide spectrum of symptoms. The first symptoms vary greatly from person to person. Some symptoms appear to be worse or have a greater effect on functional ability. These symptoms may change in severity throughout the course of the disease.

Movement disorders

The movement disorders related to Huntington’s disease may cause movements that can’t be controlled, called chorea. Chorea are involuntary movements affecting all the muscles of the body, specifically the arms and legs, the face and the tongue. They also can affect the ability to make voluntary movements. Symptoms may include:

- Involuntary jerking or writhing movements.

- Muscle rigidity or muscle contracture.

- Slow or unusual eye movements.

- Trouble walking or keeping posture and balance.

- Trouble with speech or swallowing.

People with Huntington’s disease also may not be able to control voluntary movements. This can have a greater impact than the involuntary movements caused by the disease. Having trouble with voluntary movements can affect a person’s ability to work, perform daily activities, communicate and remain independent.

Cognitive conditions

Huntington’s disease often causes trouble with cognitive skills. These symptoms may include:

- Trouble organizing, prioritizing or focusing on tasks.

- Lack of flexibility or getting stuck on a thought, behavior or action, known as perseveration.

- Lack of impulse control that can result in outbursts, acting without thinking and sexual promiscuity.

- Lack of awareness of one’s own behaviors and abilities.

- Slowness in processing thoughts or ”finding” words.

- Trouble learning new information.

Mental health conditions

The most common mental health condition associated with Huntington’s disease is depression. This isn’t simply a reaction to receiving a diagnosis of Huntington’s disease. Instead, depression appears to occur because of damage to the brain and changes in brain function. Symptoms may include:

- Irritability, sadness or apathy.

- Social withdrawal.

- Trouble sleeping.

- Fatigue and loss of energy.

- Thoughts of death, dying or suicide.

Other common mental health conditions include:

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder, a condition marked by intrusive thoughts that keep coming back and by behaviors repeated over and over.

- Mania, which can cause elevated mood, overactivity, impulsive behavior and inflated self-esteem.

- Bipolar disorder, a condition with alternating episodes of depression and mania.

Weight loss also is common in people with Huntington’s disease, especially as the disease gets worse.

Symptoms of juvenile Huntington’s disease

In younger people, Huntington’s disease begins and progresses slightly differently than it does in adults. Symptoms that may appear early in the course of the disease include:

Behavioral changes

- Trouble paying attention.

- Sudden drop in overall school performance.

- Behavioral issues, such as being aggressive or disruptive.

Physical changes

- Contracted and rigid muscles that affect walking, especially in young children.

- Slight movements that can’t be controlled, known as tremors.

- Frequent falls or clumsiness.

- Seizures.

When to see a doctor

See your healthcare professional if you notice changes in your movements, emotional state or mental ability. The symptoms of Huntington’s disease also can be caused by a number of different conditions. Therefore, it’s important to get a prompt and thorough diagnosis.

Causes

Huntington’s disease is caused by a difference in a single gene that’s passed down from a parent. Huntington’s disease follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. This means that a person needs only one copy of the nontypical gene to develop the disorder.

With the exception of genes on the sex chromosomes, a person inherits two copies of every gene — one copy from each parent. A parent with a nontypical gene could pass along the nontypical copy of the gene or the healthy copy. Each child in the family, therefore, has a 50 percent chance of inheriting the gene that causes the genetic condition.

In an autosomal dominant disorder, the changed gene is a dominant gene. It’s located on one of the nonsex chromosomes, called autosomes. Only one changed gene is needed for someone to be affected by this type of condition. A person with an autosomal dominant condition — in this example, the father — has a 50% chance of having an affected child with one changed gene and a 50% chance of having an unaffected child.

Autosomal dominant inheritance pattern Risk factors

People who have a parent with Huntington’s disease are at risk of having the disease themselves. Children of a parent with Huntington’s have a 50 percent chance of having the gene change that causes Huntington’s.

Complications

After Huntington’s disease starts, a person’s ability to function gradually gets worse over time. How quickly the disease gets worse and how long it takes varies. The time from the first symptoms to death is often about 10 to 30 years. Juvenile Huntington’s disease usually results in death within 10 to 15 years after symptoms develop.

The depression linked with Huntington’s disease may increase the risk of suicide. Some research suggests that risk of suicide is greater before a diagnosis and also when a person loses independence.

Eventually, a person with Huntington’s disease requires help with all activities of daily living and care. Late in the disease, the person will likely be confined to a bed and unable to speak. Someone with Huntington’s disease is generally able to understand language and has an awareness of family and friends, though some won’t recognize family members.

Common causes of death include:

- Pneumonia or other infections.

- Injuries related to falls.

- Complications related to trouble swallowing.

Prevention

People with a known family history of Huntington’s disease may be concerned about whether they may pass the Huntington gene on to their children. They might consider genetic testing and family planning options.

If an at-risk parent is considering genetic testing, it can be helpful to meet with a genetic counselor. A genetic counselor explains the potential risks of a positive test result, which may mean that the parent may develop the disease. Also, couples may need to make additional choices about whether to have children or to consider alternatives. They may decide to choose prenatal testing for the gene or in vitro fertilization with donor sperm or eggs.

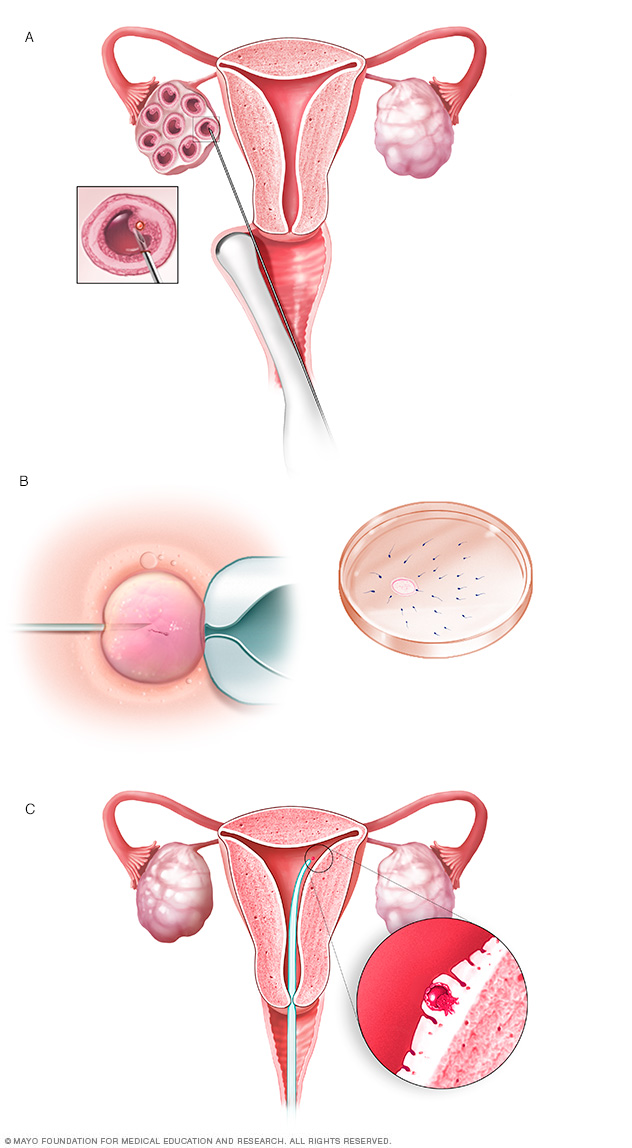

Another option for couples is in vitro fertilization and preimplantation genetic diagnosis. In this process, eggs are removed from the ovaries and fertilized with the father’s sperm in a laboratory. The embryos are tested for the presence of the Huntington gene. Only those testing negative for the Huntington gene are implanted in the mother’s uterus.

During in vitro fertilization, eggs are removed from sacs called follicles within an ovary (A). An egg is fertilized by injecting a single sperm into the egg or mixing the egg with sperm in a petri dish (B). The fertilized egg, called an embryo, is transferred into the uterus (C).

In vitro fertilization Diagnosis

A preliminary diagnosis of Huntington’s disease is based on your answers to questions, a general physical exam and your family medical history. Neurological tests and an evaluation of your mental health also is done.

Neurological exam

A neurologist asks you questions and conducts relatively simple tests of your:

- Motor symptoms, such as reflexes, muscle strength and balance.

- Sensory symptoms, including sense of touch, vision and hearing.

- Psychiatric symptoms, such as mood and mental status.

Neuropsychological testing

The neurologist also may perform standardized tests to check your:

- Memory.

- Reasoning.

- Mental agility.

- Language skills.

- Spatial reasoning.

If needed, more thorough neuropsychological testing may be done by licensed psychologists.

Mental health evaluation

You’ll likely be referred to a psychiatrist who can look for a number of factors that could contribute to your diagnosis, including:

- Emotional state.

- Patterns of behaviors.

- Quality of judgment.

- Coping skills.

- Signs of disordered thinking.

- Evidence of substance abuse.

Brain-imaging and function tests

Brain-imaging tests can provide information on the structure or function of the brain. These tests may include MRI or CT scans that show detailed images of the brain.

These images may reveal changes in the brain in areas affected by Huntington’s disease. These changes may not show up early in the course of the disease. These tests also can be used to rule out other conditions that may be causing symptoms.

Genetic counseling and testing

If symptoms strongly suggest Huntington’s disease, members of your healthcare team may recommend a genetic test for the nontypical gene.

This test can confirm the diagnosis. The test also may help if there’s no known family history of Huntington’s disease or if no other family member’s diagnosis was confirmed with a genetic test. But the test won’t provide information that might help determine a treatment plan.

Before having such a test, the genetic counselor explains the benefits and drawbacks of learning test results. The genetic counselor also can answer questions about the inheritance patterns of Huntington’s disease.

Predictive genetic test

A genetic test can be given if you have a family history of the disease but don’t have symptoms. This is called predictive testing. The test can’t tell you when the disease will begin or what symptoms will appear first.

Some people may have the test because they find not knowing to be more stressful. Others may want to take the test before having children.

Risks may include problems with insurability or future employment and the stresses of facing a fatal disease. In principle, federal laws exist that make it illegal to use genetic testing information to discriminate against people with genetic diseases.

These tests are only performed after consultation with a genetic counselor.

Treatment

No treatments can alter the course of Huntington’s disease. But medicines can lessen some symptoms of movement and mental health conditions. And multiple interventions can help a person adapt to changes in abilities for a certain amount of time.

The medicines you take may change over the course of the disease, depending on your overall treatment goals. Also, medicines that treat some symptoms may result in side effects that worsen other symptoms. Treatment goals are regularly reviewed and updated.

Medicines for movement disorders

Medicines to treat movement disorders include:

- Medicines to control movement include tetrabenazine (Xenazine), deutetrabenazine (Austedo) and valbenazine (Ingrezza). They have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to suppress involuntary jerking and writhing movements, known as chorea. Chorea can happen as a result of Huntington’s disease. These medicines don’t affect how the disease progresses, however. Possible side effects include drowsiness, restlessness, and the risk of worsening or triggering depression or other psychiatric conditions.

- Antipsychotic medicines, such as haloperidol and fluphenazine, olanzapine (Zyprexa) and aripiprazole (Abilify, Aristada) have a side effect of suppressing movements. Therefore, they may help to treat chorea. However, these medicines may worsen involuntary muscle contractions called dystonia and cause slowness of movements, resembling Parkinson’s disease. They also may cause restlessness and drowsiness.

- Other medicines that may help suppress chorea include amantadine (Gocovri), levetiracetam (Keppra, Spritam) and clonazepam (Klonopin). However, mild effectiveness and side effects may limit their use.

Medicines for mental health conditions

Medicines to treat mental health vary depending on the conditions and symptoms. Possible treatments include:

- Antidepressants include citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac) and sertraline (Zoloft). These medicines also may have some effect on obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms. Side effects may include nausea, diarrhea, drowsiness and low blood pressure.

- Antipsychotic medicines such as quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa) may suppress violent outbursts, agitation and other symptoms. However, these medicines may cause different movement disorders themselves.

- Mood-stabilizing medicines can help prevent the highs and lows associated with bipolar disorder. They include anti-seizure medicines such as divalproex (Depakote), carbamazepine (Tegretol, Carbatrol, Epitol, others) and lamotrigine (Lamictal).

Psychotherapy

A psychotherapist — a psychiatrist, psychologist or clinical social worker — can provide talk therapy to help with behavioral symptoms. The psychotherapist can help you and your family develop coping strategies, manage expectations as the disease gets worse and help family members communicate.

Speech therapy

Huntington’s disease can affect the control of muscles of the mouth and throat that are essential for speech, eating and swallowing. A speech therapist can help improve your ability to speak clearly or teach you to use communication devices. A communication device might be as simple as a board covered with pictures of everyday items and activities. Speech therapists also can address trouble with eating and swallowing.

Physical therapy

A physical therapist can teach you proper and safe exercises that enhance strength, flexibility, balance and coordination. These exercises can help maintain mobility as long as possible and may reduce the risk of falls.

Instruction on posture and the use of supports to improve posture may help lessen some movement symptoms.

When you need a walker or wheelchair, the physical therapist can advise on the proper use of the device and posture. Also, exercises can be adapted for your level of mobility.

Occupational therapy

An occupational therapist can assist you, your family members and caregivers on how to use assistive devices to improve function. These strategies may include:

- Handrails at home.

- Assistive devices for activities such as bathing and dressing.

- Eating and drinking utensils adapted for people with limited fine motor skills.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Managing Huntington’s disease affects the person with the disease, family members and other in-home caregivers. As the disease gets worse, the person becomes more dependent on caregivers. Several issues need to be addressed, and the ways to cope with them changes over time.

Eating and nutrition

Factors regarding eating and nutrition include the following:

- Trouble maintaining a healthy body weight. This may be caused by having trouble eating or by needing more calories due to physical exertion or a metabolic condition. To get enough nutrition, you may need to eat more than three meals a day or use dietary supplements.

- Trouble with chewing, swallowing and fine motor skills. This can limit the amount of food you eat and increase the risk of choking. It may help to remove distractions during a meal and select foods that are easier to eat. Utensils designed for people with limited fine motor skills and covered cups with straws or drinking spouts also can help.

Eventually, a person with Huntington’s disease needs help with eating and drinking.

Managing cognitive and mental health conditions

Family and caregivers can help create an environment that may help a person with Huntington’s disease avoid things that cause stress. This can help manage cognitive and behavioral symptoms. These strategies include:

- Using calendars and schedules to help keep a regular routine.

- Starting tasks with reminders or assistance.

- Organizing work or activities in order of importance.

- Breaking down tasks into manageable steps.

- Creating an environment that is as calm, simple and structured as possible.

- Looking for and steering away from stressors that can trigger outbursts, irritability, depression or other symptoms.

- For school-age children or teenagers, talking with school staff to develop an individual education plan.

- Providing chances for the person to maintain social interactions and friendships as much as possible.

Coping and support

A number of strategies may help people with Huntington’s disease and their families cope.

Support services

Support services for people with Huntington’s disease and families include the following:

- Nonprofit agencies, such as the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, provide caregiver education. They also can offer referrals to outside services and support groups for people with the disease and caregivers.

- Local and state health or social service agencies may provide daytime care for people with the disease, meal assistance programs or respite for caregivers.

Planning for residential and end-of-life care

Huntington’s disease causes a loss of function and eventually death. It’s important to plan for care that will be needed in the advanced stages of the disease and near the end of life. Early discussions about care allow the person with Huntington’s disease to be engaged and to share what they want from their care.

Creating legal documents that define end-of-life care can be helpful to everyone. They empower the person with the disease, and they may prevent conflict among family members as the disease gets worse. Members of your healthcare team can offer advice on the pluses and minuses of care options.

Matters that may need to be addressed include:

- Care facilities. In-home nursing care or care in an assisted living facility or nursing home is needed during the advanced stages of the disease.

- Hospice care. Hospice services provide care at the end of life that helps a person approach death with as little discomfort as possible. This care also provides support and education to family members to help them understand the process of dying.

- Living wills. Living wills are legal documents that enable a person to spell out care preferences when it isn’t possible to make decisions. For example, these directions might say whether or not the person wants life-sustaining interventions or aggressive treatment of an infection.

- Advance directives. These legal documents allow you to choose one or more people to make decisions on your behalf. You may create an advance directive for medical decisions or financial matters.

Preparing for an appointment

If you have any symptoms of Huntington’s disease, you’ll likely be referred to a neurologist after a visit to your healthcare professional.

A review of your symptoms, mental state, medical history and family medical history can all be important when assessing a potential neurological disorder.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list that includes the following:

- Symptoms or any changes from what is usual for you that may be causing concern.

- Recent changes or stresses in your life.

- All medicines, including any available without a prescription and dietary supplements. Include the doses you take.

- Family history of Huntington’s disease or other conditions that may cause movement disorders or mental health conditions.

You may want a family member or friend to come with you to your appointment. This person can provide support and offer a different perspective on the effect of symptoms on your functional abilities.

What to expect from your doctor

You’re likely to be asked a number of questions, including the following:

- When did you begin experiencing symptoms?

- Have your symptoms been constant or do they occur off and on?

- Has anyone in your family ever been diagnosed with Huntington’s disease?

- Has anyone in your family been diagnosed with another movement disorder or mental health condition?

- Are you having trouble completing work, schoolwork or daily tasks?

- Has anyone in your family died young?

- Is anyone in your family in a nursing home?

- Is anyone in your family fidgety or moving all the time?

- Have you noticed a change in your general mood?

- Do you feel sad all of the time?

- Have you ever thought about suicide?