Congenital heart defects in children

![]() September, 25th, 2024

September, 25th, 2024

Benefit Summary

Learn about symptoms, tests and treatments for children born with a problem in the structure of the heart.

Overview

, Overview, ,

A congenital heart defect is a problem with the structure of the heart that a child is born with.

Some congenital heart defects in children are simple and don’t need treatment. Others are more complex. The child may need several surgeries done over a period of several years.

Symptoms

Serious congenital heart defects usually are found soon after birth or during the first few months of life. Symptoms could include:

- Pale gray or blue lips, tongue, or fingernails. Depending on the skin color, these changes may be harder or easier to see.

- Rapid breathing.

- Swelling in the legs, belly or areas around the eyes.

- Shortness of breath during feedings, leading to poor weight gain.

Less-serious congenital heart defects may not be found until later in childhood. Symptoms of congenital heart defects in older children may include:

- Easily getting short of breath during exercise or activity.

- Getting tired very easily during exercise or activity.

- Fainting during exercise or activity.

- Swelling in the hands, ankles or feet.

When to see a doctor

Serious congenital heart defects are often diagnosed before or soon after a child is born. If you think that your baby has symptoms of a heart condition, call your child’s healthcare professional.

Causes

To understand the causes of congenital heart defects, it may help to know how the heart usually works.

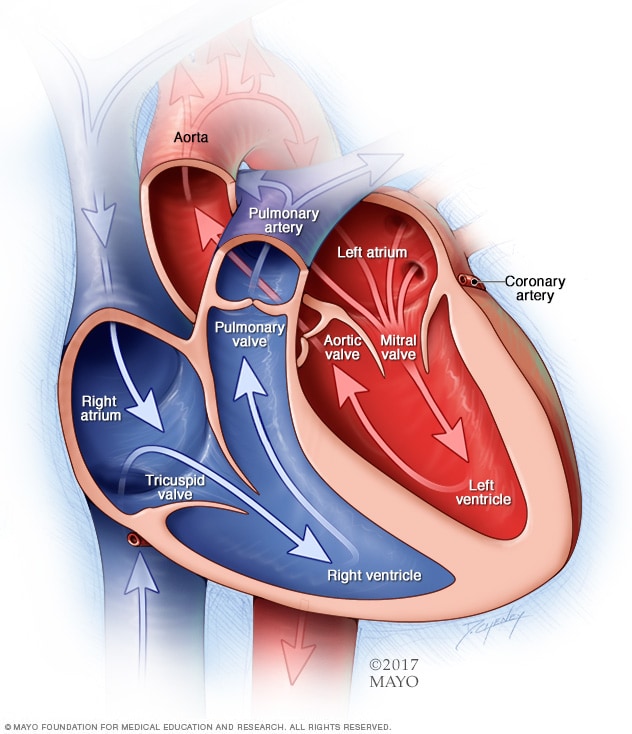

The typical heart has four chambers. There are two on the right and two on the left.

- The two upper chambers are called the atria.

- The two lower chambers are called the ventricles.

To pump blood through the body, the heart uses its left and right sides for different tasks.

- The right side of the heart moves blood to the lungs through the lung arteries, called the pulmonary arteries.

- In the lungs, the blood gets oxygen. The blood then goes to the heart’s left side through the pulmonary veins.

- The left side of the heart pumps the blood through the body’s main artery, called the aorta. It then goes to the rest of the body.

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of the heart. The heart valves are gates at the chamber openings. They keep blood flowing in the right direction.

Chambers and valves of the heart Symptoms

How congenital heart defects develop

During the first six weeks of pregnancy, the baby’s heart begins to form and starts to beat. The major blood vessels that go to and from the heart also begin to form during this critical time.

It’s at this point in a baby’s development that congenital heart defects may begin to develop. Researchers aren’t sure what causes most types of congenital heart defects. They think that gene changes, certain medicines or health conditions, and environmental or lifestyle factors, such as smoking, may play a role.

There are many types of congenital heart defects. They fall into the general categories described below.

Changes in the connections in the heart or blood vessels

Changes in connections, also called altered connections, let blood flow where it usually wouldn’t.

An altered connection can cause oxygen-poor blood to mix with oxygen-rich blood. This lowers the amount of oxygen sent through the body. The change in blood flow forces the heart and lungs to work harder.

Types of altered connections in the heart or blood vessels include:

- Atrial septal defect is a hole between the upper heart chambers, called the atria.

- Ventricular septal defect is a hole in the wall between the right and left lower heart chambers, called the ventricles.

- Patent ductus arteriosus (PAY-tunt DUK-tus ahr-teer-e-O-sus) is a connection between the lung artery and the body’s main artery, called the aorta. It’s open while a baby is growing in the womb, and typically closes a few hours after birth. But in some babies, it stays open, causing incorrect blood flow between the two arteries.

- Total or partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection occurs when all or some of the blood vessels from the lungs, called the pulmonary veins, attach to a wrong area or areas of the heart.

Congenital heart valve problems

Heart valves are like doorways between the heart chambers and the blood vessels. Heart valves open and close to keep blood moving in the proper direction. If the heart valves can’t open and close correctly, blood can’t flow smoothly.

Heart valve problems include valves that are narrowed and don’t open completely or valves that don’t close completely.

Examples of congenital heart valve problems include:

- Aortic stenosis (stuh-NO-sis). A baby may be born with an aortic valve that has one or two valve flaps, called cusps, instead of three. This creates a small, narrowed opening for blood to pass through. The heart must work harder to pump blood through the valve. Eventually, the heart gets bigger and the heart muscle gets thicker.

- Pulmonary stenosis. The pulmonary valve opening is narrowed. This slows the blood flow.

- Ebstein anomaly. The tricuspid valve — which is located between the right upper heart chamber and the right lower chamber — is not its usual shape. It often leaks.

Combination of congenital heart defects

Some infants are born with several congenital heart defects. Very complex ones may cause significant changes in blood flow or undeveloped heart chambers.

Examples include:

- Tetralogy of Fallot (teh-TRAL-uh-jee of fuh-LOW). There are four changes to the heart’s shape and structure. There’s a hole in the wall between the heart’s lower chambers and thickened muscle in the lower right chamber. The path between the lower heart chamber and pulmonary artery is narrowed. There also is a shift in the connection of the aorta to the heart.

- Pulmonary atresia. The valve that lets blood out of the heart to go to the lungs, called the pulmonary valve, isn’t formed correctly. Blood can’t travel its usual path to get oxygen from the lungs.

- Tricuspid atresia. The tricuspid valve isn’t formed. Instead, there’s solid tissue between the right upper heart chamber and the right lower chamber. This condition limits blood flow. It causes the right lower chamber to be underdeveloped.

- Transposition of the great arteries. In this serious, rare congenital heart defect, the two main arteries leaving the heart are reversed, also called transposed. There are two types. Complete transposition of the great arteries is typically noticed during pregnancy or soon after birth. It also is called dextro-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA). Levo-transposition of the great arteries (L-TGA) is less common. Symptoms may not be noticed right away.

- Hypoplastic left heart syndrome. A major part of the heart fails to develop properly. The left side of the heart hasn’t developed enough to successfully pump enough blood to the body.

Risk factors

Most congenital heart defects result from changes that occur early as the baby’s heart is developing before birth. The exact cause of most congenital heart defects is unknown. But some risk factors have been identified.

Risk factors for congenital heart defects include:

- Rubella, also called German measles. Having rubella during pregnancy can cause changes in a baby’s heart development. A blood test done before pregnancy can determine if you’re immune to rubella. A vaccine is available for those who aren’t immune.

- Diabetes. Careful control of blood sugar before and during pregnancy can reduce the risk of congenital heart defects in the baby. Diabetes that develops during pregnancy is called gestational diabetes. It generally doesn’t increase a baby’s risk of heart defects.

- Some medicines. Taking certain medicines during pregnancy can cause congenital heart disease and other health problems present at birth. Medicines linked to congenital heart defects include lithium (Lithobid) for bipolar disorder and isotretinoin (Claravis, Myorisan, others), which is used to treat acne. Always tell your healthcare team about the medicines you take.

- Drinking alcohol during pregnancy. Drinking alcohol during pregnancy increases the risk of congenital heart defects in the baby.

- Smoking. If you smoke, quit. Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of congenital heart defects in the baby.

- Genetics. Congenital heart defects appear to run in families, which means they are inherited. Changes in genes have been linked to heart problems present at birth. For instance, people with Down syndrome are often born with heart conditions.

Complications

Possible complications of a congenital heart defect include:

- Congestive heart failure. This serious complication may develop in babies who have a severe congenital heart defect. Symptoms of congestive heart failure include rapid breathing, often with gasping breaths, and poor weight gain.

- Infection of the lining of the heart and heart valves, called endocarditis. Untreated, this infection can damage or destroy the heart valves or cause a stroke. Antibiotics may be recommended before dental care to prevent this infection. Regular dental checkups are important. Healthy gums and teeth reduce the risk of endocarditis.

- Irregular heartbeats, called arrhythmias. Scar tissue in the heart from surgeries to fix a congenital heart condition can lead to changes in heart signaling. The changes can cause the heart to beat too fast, too slow or irregularly. Some irregular heartbeats may cause stroke or sudden cardiac death if not treated.

- Slower growth and development (developmental delays). Children with more-serious congenital heart defects often develop and grow more slowly than do children who don’t have heart defects. They may be smaller than other children of the same age. If the nervous system has been affected, a child may learn to walk and talk later than other children.

- Stroke. Although uncommon, a congenital heart defect can let a blood clot pass through the heart and travel to the brain, causing a stroke.

- Mental health disorders. Some children with congenital heart defects may develop anxiety or stress because of developmental delays, activity restrictions or learning difficulties. Talk to your child’s healthcare professional if you’re concerned about your child’s mental health.

Complications of congenital heart defects may occur years after the heart condition is treated.

Prevention

Because the exact cause of most congenital heart defects is unknown, it may not be possible to prevent these conditions. If you have a high risk of giving birth to a child with a congenital heart defect, genetic testing and screening may be done during pregnancy.

There are some steps you can take to help reduce your child’s overall risk of heart problems present at birth such as:

- Get proper prenatal care. Regular checkups with a healthcare professional during pregnancy can help keep mom and baby healthy.

- Take a multivitamin with folic acid. Taking 400 micrograms of folic acid daily has been shown to prevent harmful changes in the baby’s brain and spinal cord. It also may help reduce the risk of congenital heart defects as well.

- Don’t drink or smoke. These lifestyle habits can harm a baby’s health. Also avoid secondhand smoke.

- Get a rubella vaccine. Also called German measles, having rubella during pregnancy may affect a baby’s heart development. Get vaccinated before trying to get pregnant.

- Control blood sugar. If you have diabetes, good control of your blood sugar can reduce the risk of congenital heart defects.

- Manage chronic health conditions. If you have other health conditions, talk to your healthcare professional about the best way to treat and manage them.

- Avoid harmful substances. During pregnancy, have someone else do any painting and cleaning with strong-smelling products.

- Tell your care team about your medicines. Some medicines can cause congenital heart defects and other health conditions present at birth. Tell your care team about all the medicines you take, including those bought without a prescription.

Diagnosis

A congenital heart defect may be diagnosed during pregnancy or after birth. Signs of certain heart defects can be seen on a routine pregnancy ultrasound test (fetal ultrasound).

After a baby is born, a healthcare professional might think there’s a congenital heart defect if the baby has:

- Growth delays.

- Color changes in the lips, tongues or nails.

The healthcare professional may hear a sound, called a murmur, while listening to the child’s heart with a stethoscope. Most heart murmurs are innocent, meaning that there is no heart defect and the murmur isn’t dangerous to your child’s health. However, some murmurs may be caused by blood flow changes to and from the heart.

Tests

Tests to diagnose a congenital heart defect include:

- Pulse oximetry. A sensor placed on the fingertip records the amount of oxygen in the blood. Too little oxygen may be a sign of a heart or lung problem.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This quick test records the electrical activity of the heart. It shows how the heart is beating. Sticky patches with sensors, called electrodes, attach to the chest and sometimes the arms or legs. Wires connect the patches to a computer, which prints or displays results.

- Echocardiogram. Sound waves are used to create images of the heart in motion. An echocardiogram shows how blood moves through the heart and heart valves. If the test is done on a baby before birth, it’s called a fetal echocardiogram.

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray shows the condition of the heart and lungs. It can show if the heart is enlarged, or if the lungs contain extra blood or other fluid. These could be signs of heart failure.

- Cardiac catheterization. In this test, a doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube called a catheter into a blood vessel, usually in the groin area, and guides it to the heart. This test can give detailed information on blood flow and how the heart works. Some heart treatments can be done during cardiac catheterization.

- Heart MRI. Also called a cardiac MRI, this test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the heart. A cardiac MRI may be done to diagnose and evaluate congenital heart defects in adolescents and adults. A heart MRI creates 3D pictures of the heart, which allows for accurate measurement of the heart chambers.

A 2D fetal ultrasound can help your healthcare professional evaluate your baby’s growth and development.

A 2D fetal ultrasound can help your healthcare professional evaluate your baby’s growth and development.

2D fetal ultrasound Treatment

Treatment of congenital heart defects in children depends on the specific heart problem and how severe it is.

Some congenital heart defects don’t have a long-term effect on a child’s health. They may safely go untreated.

Other congenital heart defects, such as a small hole in the heart, may close as a child ages.

Serious congenital heart defects need treatment soon after they’re found. Treatment may include:

- Medicines.

- Heart procedures.

- Heart surgery.

- Heart transplant.

Medications

Medicines may be used to treat symptoms or complications of a congenital heart defect. They may be used alone or with other treatments. Medicines for congenital heart defects include:

- Blood pressure drugs. Examples include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin 2 receptor blockers (ARBs) and beta blockers.

- Water pills, also called diuretics. This type of medicine helps remove fluid from the body. They help lower the strain on the heart.

- Heart rhythm drugs, called anti-arrhythmics. These medicines help control irregular heartbeats.

Surgery or other procedures

If your child has a severe congenital heart defect, a heart procedure or surgery may be recommended.

Heart procedures and surgeries done to treat congenital heart defects include:

- Cardiac catheterization. Some types of congenital heart defects in children can be repaired using thin, flexible tubes called catheters. Such treatments let doctors fix the heart without open-heart surgery. The doctor inserts a catheter through a blood vessel, usually in the groin, and guides it to the heart. Sometimes more than one catheter is used. Once in place, the doctor threads tiny tools through the catheter to fix the heart condition. For example, the surgeon may fix holes in the heart or areas of narrowing. Some catheter treatments have to be done in steps over a period of years.

- Heart surgery. A child may need open-heart surgery or minimally invasive heart surgery to repair a congenital heart defect. The type of heart surgery depends on the specific change in the heart.

- Heart transplant. If a serious congenital heart defect can’t be fixed, a heart transplant may be needed.

- Fetal cardiac intervention. This is a type of treatment for a baby with a heart problem that’s done before birth. It may be done to fix a serious congenital heart defect or prevent complications as the baby grows during pregnancy. Fetal cardiac intervention is rarely done and is only possible in very specific situations.

Some children born with a congenital heart defect need many procedures and surgeries throughout life. Lifelong follow-up care is important. The child needs regular health checkups by a doctor trained in heart diseases, called a cardiologist. Follow-up care may include blood and imaging tests to check for complications.

Lifestyle and home remedies

If your child has a congenital heart defect, lifestyle changes may be recommended to keep the heart healthy and prevent complications.

- Sports and activity restrictions. Some children with a congenital heart defect may need to reduce exercise or sports activities. However, many others with a congenital heart defect can participate in such activities. Your child’s care professional can tell you which sports and types of exercise are safe for your child.

- Preventive antibiotics. Some congenital heart defects can increase the risk of infection in the lining of the heart or heart valves, called infective endocarditis. Antibiotics may be recommended before dental procedures to prevent infection, especially for people who have a mechanical heart valve. Ask your child’s heart doctor if your child needs preventive antibiotics.

Coping and support

You may find that talking with other people who have been through the same situation brings you comfort and encouragement. Ask your healthcare team if there are any support groups in your area.

Living with a congenital heart defect may make some children feel stressed or anxious. Talking to a counselor may help you and your child learn new ways to manage stress and anxiety. Ask a healthcare professional for information about counselors in your area.

Preparing for an appointment

A life-threatening congenital heart defect is usually diagnosed soon after birth. Some may be discovered before birth during a pregnancy ultrasound.

If you think your child has symptoms of a heart condition, talk to your child’s healthcare professional. Be prepared to describe your child’s symptoms and provide a family medical history. Some congenital heart defects tend to be passed down through families. That means they are inherited.

What you can do

When you make the appointment, ask if there’s anything your child needs to do in advance, such as avoiding food or drinks for a short period of time.

Make a list of:

- Your child’s symptoms, if any. Include those that may seem unrelated to congenital heart defects. Also note when they started.

- Important personal information, including a family history of congenital heart defects.

- Any infections or health conditions the child’s birth mother has or had and if alcohol was used during pregnancy.

- All medicines, vitamins or other supplements taken during pregnancy. Also include a list of medicines your child takes. Include those bought without a prescription. Also include the dosages.

- Questions to ask your healthcare team.

Preparing a list of questions can help you and your healthcare team make the most of your time together. If your child is diagnosed with a congenital heart defect, ask the specific name of the condition.

Questions to ask the healthcare professional might include:

- What tests does my child need? Do these tests need any special preparation?

- Does my child need treatment? If so, when?

- What is the best treatment?

- Is my child at risk of long-term complications?

- How can we watch for possible complications?

- If I have more children, how likely are they to have a congenital heart defect?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take home with me? What websites do you recommend visiting?

What to expect from your doctor

Your child’s healthcare team may ask you many questions. Being ready to answer them may save time to go over any details you want to spend more time on. The healthcare team may ask:

- When did you first notice your child’s symptoms?

- How would you describe your child’s symptoms?

- When do these symptoms occur?

- Do the symptoms come and go, or does your child always have them?

- Do the symptoms seem to be getting worse?

- Does anything make your child’s symptoms better?

- Do you have a family history of congenital heart defects or congenital heart disease?

- Has your child been growing and meeting developmental milestones as expected? (Ask your child’s pediatrician if you’re not sure.)