Aortic valve regurgitation

![]() November, 20th, 2024

November, 20th, 2024

Benefit Summary

Learn more about the symptoms and treatment of this condition in which the heart’s aortic valve doesn’t close tightly.

Overview

, Overview, ,

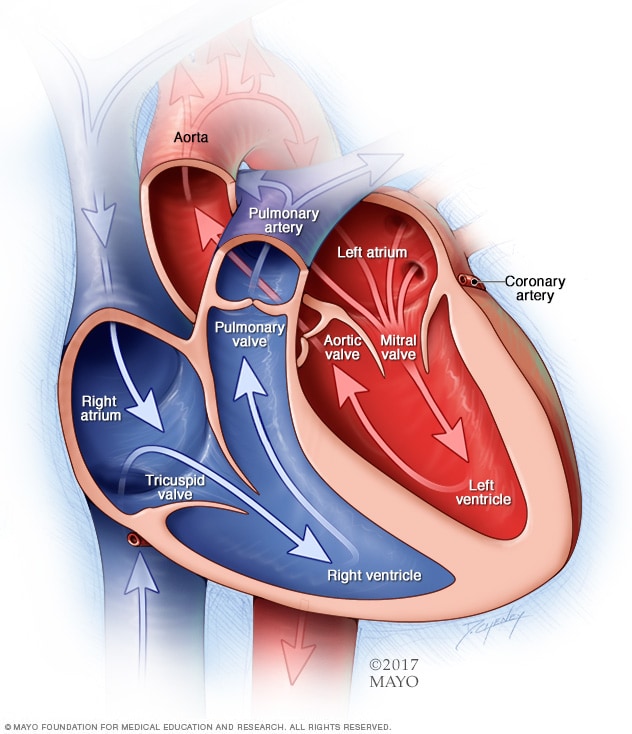

Aortic valve regurgitation — also called aortic regurgitation — is a type of heart valve disease. The valve between the lower left heart chamber and the body’s main artery doesn’t close tightly. As a result, some of the blood pumped out of the heart’s main pumping chamber, called the left ventricle, leaks backward.

The leakage may prevent the heart from doing a good enough job of pumping blood to the rest of the body. You may feel tired and short of breath.

Aortic valve regurgitation can develop suddenly or over many years. Once the condition becomes severe, surgery often is needed to repair or replace the valve.

In aortic valve regurgitation, the aortic valve doesn’t close properly. This causes blood to flow backward from the body’s main artery, called the aorta, into the lower left heart chamber, called the left ventricle.

In aortic valve regurgitation, the aortic valve doesn’t close properly. This causes blood to flow backward from the body’s main artery, called the aorta, into the lower left heart chamber, called the left ventricle.

Aortic valve regurgitation Symptoms

Most often, aortic valve regurgitation develops over time. You may have no symptoms for years. You might not realize that you have the condition. But sometimes, aortic valve regurgitation occurs suddenly. Usually, this is due to an infection of the valve.

As aortic valve regurgitation becomes worse, symptoms may include:

- Shortness of breath with exercise or when lying down.

- Tiredness and weakness, especially when being more active than usual.

- Irregular heartbeat.

- Lightheadedness or fainting.

- Pain, discomfort or tightness in the chest, which often gets worse during exercise.

- Sensations of a rapid, fluttering heartbeat, called palpitations.

- Swollen ankles and feet.

When to see a doctor

Call a member of your health care team right away if you have symptoms of aortic valve regurgitation.

Sometimes the first symptoms of aortic valve regurgitation are related to heart failure. Heart failure is a condition in which the heart can’t pump blood as well as it should. Make an appointment with your health care team if you have:

- Tiredness, also called fatigue, that doesn’t get better with rest.

- Shortness of breath.

- Swollen ankles and feet.

These are common symptoms of heart failure.

Causes

The aortic valve is one of four valves that control blood flow through the heart. It separates the heart’s main pumping chamber, called the left ventricle, and the body’s main artery, called the aorta. The aortic valve has flaps, also called cusps or leaflets, that open and close once during each heartbeat.

In aortic valve regurgitation, the valve doesn’t close properly. This causes blood to leak back into the lower left heart chamber, called the left ventricle. As a result, the chamber holds more blood. This could cause it to get larger and thicken.

At first, the larger left ventricle helps maintain good blood flow with more force. But eventually, the heart becomes weak.

Any condition that damages the aortic valve can cause aortic valve regurgitation. Causes may include:

-

Heart valve disease present at birth. Some people are born with an aortic valve that has only two cusps, called a bicuspid valve. Others are born with connected cusps rather than the typical three separate ones. Sometimes the valve may have only one cusp, called a unicuspid valve. Other times, there are four cusps, called a quadricuspid valve.

Having a parent or sibling with a bicuspid valve raises your risk of the condition. But you can have a bicuspid valve even if you don’t have a family history of the condition.

- Narrowing of the aortic valve, called aortic stenosis. Calcium deposits can build up on the aortic valve as you age. The buildup causes the aortic valve to stiffen and become narrow. It prevents the valve from opening properly. Aortic stenosis also may prevent the valve from closing properly.

- Inflammation of the inner lining of the heart’s chambers and valves. This life-threatening condition also is called endocarditis. It’s usually caused by an infection. It can damage the aortic valve.

- Rheumatic fever. This condition was once a common childhood illness in the United States. Strep throat can cause it. Rheumatic fever can cause the aortic valve to become stiff and narrow, in turn causing blood to leak. If you have an irregular heart valve due to rheumatic fever, it’s called rheumatic heart disease.

- Other health conditions. Other rare conditions can cause the aorta to get bigger and damage the aortic valve. These include a connective tissue disease called Marfan syndrome. Some immune system conditions, such as lupus, also can lead to aortic valve regurgitation.

- Tear or injury of the body’s main artery. The body’s main artery is the aorta. A traumatic chest injury may damage the aorta and cause aortic regurgitation. So might a tear in the inner layer of the aorta, called an aortic dissection.

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers, the right and left atria, receive incoming blood. The lower chambers, the more muscular right and left ventricles, pump blood out of the heart. The heart valves are gates at the chamber openings. They keep blood flowing in the right direction.

Chambers and valves of the heart Risk factors

Things that raise the risk of aortic valve regurgitation include:

- Older age.

- Heart problems present at birth, also called congenital heart defects.

- History of infections that can affect the heart.

- Certain conditions passed down through families that can affect the heart, such as Marfan syndrome.

- Other types of heart valve disease, such as aortic valve stenosis.

- High blood pressure.

The condition also can happen without any known risk factors.

Complications

Complications of aortic valve regurgitation can include:

- Fainting or feeling lightheaded.

- Heart failure.

- Certain heart infections such as endocarditis.

- Heart rhythm problems, called arrhythmias.

- Death.

Prevention

If you have any type of heart disease, get regular health checkups.

If you have a parent, child or sibling with a bicuspid aortic valve, you should have an imaging test called an echocardiogram. This can check for aortic valve regurgitation. Early diagnosis of heart valve disease, such as aortic valve regurgitation, is important. Doing so may make the condition easier to treat.

Also, take steps to prevent conditions that can raise the risk of aortic valve regurgitation. For example:

- Get a health checkup if you have a severe sore throat. Untreated strep throat can lead to rheumatic fever. Strep throat is treated with medicines that fight bacteria, called antibiotics.

- Check your blood pressure regularly. Have your blood pressure checked at least every two years starting at age 18. Some people need more-frequent checks.

Diagnosis

To diagnose aortic valve regurgitation, a member of your health care team examines you. You usually are asked questions about your symptoms and health history. You also might be asked about your family’s health history.

Your blood pressure is checked using a cuff, usually placed around your arm. A device called a stethoscope is used to listen to your heart. Your health care professional may hear an irregular sound called a heart murmur.

You may be referred to a doctor trained in heart diseases, called a cardiologist.

Treatment

Treatment of aortic valve regurgitation depends on:

- How serious the condition is.

- The symptoms, if any.

- Whether the condition is getting worse.

The goals of aortic valve regurgitation treatment are to ease symptoms and prevent complications.

If your symptoms are mild or you don’t have symptoms, you may only need regular health checkups. You may need regular echocardiograms to check the health of the aortic valve. Heart-healthy lifestyle changes also are usually recommended.

Medications

If you have aortic valve regurgitation, you may be given medicines to:

- Treat symptoms.

- Reduce the risk of complications.

- Lower blood pressure.

Surgery or other procedures

Surgery may be needed to repair or replace the diseased valve, especially if the condition and symptoms are severe. Heart valve surgery may be needed even if aortic regurgitation isn’t severe or when there are no symptoms.

The decision to repair or replace a damaged aortic valve depends on:

- Your symptoms.

- Your age and overall health.

- Whether you need heart surgery to correct another heart condition.

If you’re having another heart surgery, surgeons may do aortic valve surgery at the same time.

Surgery to repair or replace an aortic valve may be done as open-heart surgery. This involves a cut, also called an incision, in the chest. Sometimes surgeons can do minimally invasive heart surgery to replace the aortic valve.

Surgery for aortic valve regurgitation includes:

- Aortic valve repair. To repair an aortic valve, surgeons may separate valve flaps, also called cusps, that have connected. They might reshape or remove excess valve tissue so that the cusps can close tightly. Or they might patch holes in a valve. A catheter procedure may be done to place a plug or device in a leaking replacement aortic valve.

-

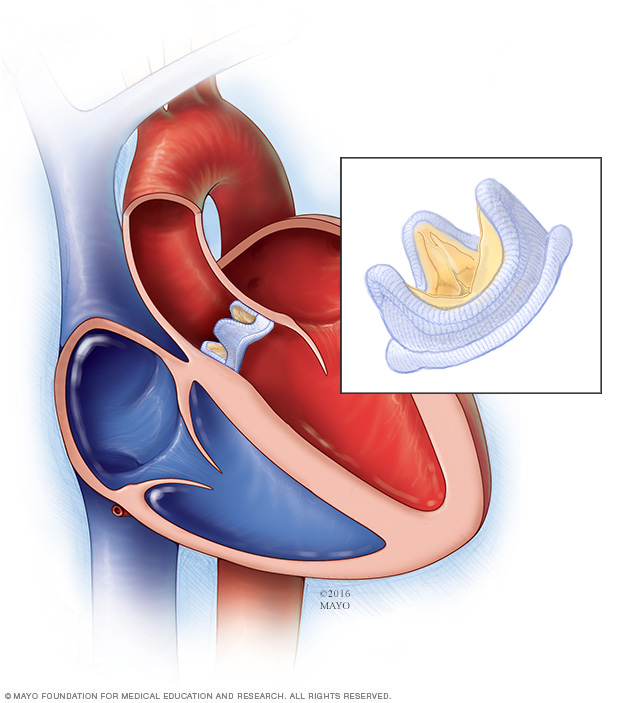

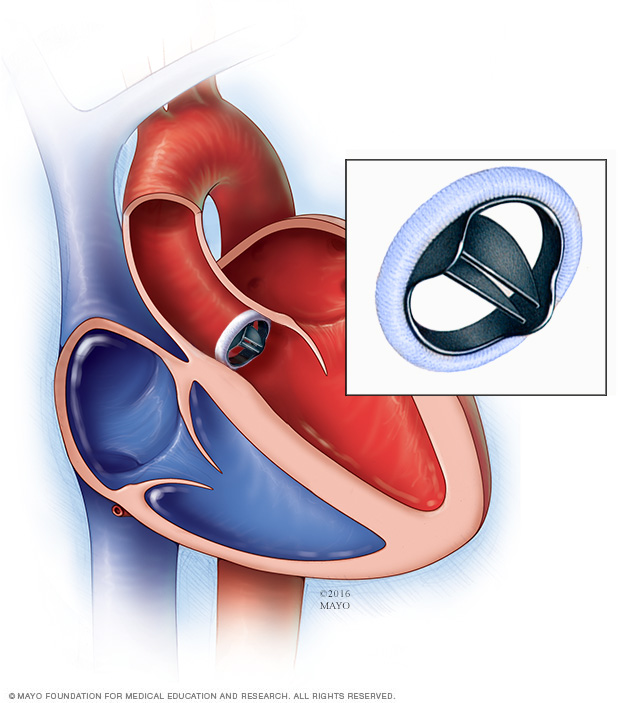

Aortic valve replacement. The surgeon removes the damaged valve and replaces it. The replacement might be a mechanical valve or one made from cow, pig or human heart tissue. A tissue valve also is called a biological tissue valve.

Sometimes, surgeons can do minimally invasive heart surgery to replace the aortic valve. This procedure is called transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). It uses smaller incisions than those used in open-heart surgery.

Sometimes the aortic valve is replaced with your own lung valve, also called the pulmonary valve. Your pulmonary valve is replaced with a biological lung tissue valve from a deceased donor. This more complicated surgery is called the Ross procedure.

Biological tissue valves break down over time. Eventually, they may need to be replaced. People with mechanical valves need blood thinners for life to prevent blood clots. Ask your health care team about the benefits and risks of each type of valve.

In a biological valve replacement, a valve made from cow, pig or human heart tissue replaces the damaged heart valve.

In a mechanical valve replacement, an artificial heart valve made of strong material replaces the damaged valve.

Mechanical valve replacement Lifestyle and home remedies

While lifestyle changes can’t prevent or treat your condition, your health care team might suggest that you practice some heart-healthy habits. These may include:

- Eat a heart-healthy diet. Enjoy a variety of fruits and vegetables, low-fat or fat-free dairy products, poultry, fish, and whole grains. Stay away from saturated and trans fats and excess salt and sugar.

- Stay at a healthy weight. Aim to keep a healthy weight. If you’re overweight or obese, your health care team may recommend that you lose weight. Ask what goal weight is healthy for you.

- Get regular exercise. Aim to include about 30 minutes of physical activity, such as brisk walks, into your daily fitness routine. Ask your care team for advice before you start to exercise, especially if you’re thinking about playing competitive sports.

- Don’t smoke or use tobacco. If you smoke, quit. Ask your care team about resources to help you quit smoking. Joining a support group may be helpful.

- Control high blood pressure. Uncontrolled high blood pressure increases the risk of serious health problems. Get your blood pressure checked at least every two years if you’re 18 or older. If you have risk factors for heart disease or are over age 40, you may need more-frequent checks.

- Get a cholesterol test. Get your first cholesterol test when you’re in your 20s and then another at least every 4 to 6 years. Some people may need to start testing earlier or have more-frequent checks.

- Manage diabetes. If you have diabetes, tight blood sugar control can help keep your heart healthy.

- Practice good sleep habits. Poor sleep may increase the risk of heart disease. Adults should aim to get 7 to 9 hours of sleep daily. Go to bed and wake at the same time every day, including on weekends. If you have trouble sleeping, talk with your health care team about strategies that might help.

Pregnancy and aortic valve regurgitation

Careful and regular checkups are needed for those who have heart valve disease, including aortic valve regurgitation, during pregnancy. If you have a severe heart valve condition, you might be told not to get pregnant to reduce the risk of complications.

Preparing for an appointment

If you think you might have symptoms of heart valve disease, make an appointment for a health checkup. You may be referred to a doctor trained in heart diseases. This doctor is called a cardiologist.

If you have aortic valve regurgitation, consider being cared for by a medical team that specializes in heart valve disease.

Here’s some information to help you prepare for your appointment.

What you can do

- Be aware of pre-appointment restrictions. When you make the appointment, ask if there’s anything you need to do in advance. For example, you may be told not to eat or drink for a short period before a cholesterol test.

- Write down your symptoms and how long you’ve had them. Include any that seem unrelated to heart valve disease.

- Write down important medical information, including any family history of heart valve disease, and any major stresses or recent life changes.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins and supplements you take. Include dosages.

- Take a family member or friend with you to the appointment, if possible. Someone who joins you can help remember what your health care team says.

- Write down questions to ask your health care team.

For aortic valve regurgitation, questions to ask your health care team include:

- What is the likely cause of my symptoms?

- Are there any other possible causes?

- What tests do I need?

- What treatment do you recommend?

- Are there any other treatment options?

- Will I need surgery? If so, what surgeon do you recommend for aortic valve surgery?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there restrictions I need to follow?

- Should I see a specialist?

Don’t hesitate to ask any other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

You are usually asked many questions, including:

- When did your symptoms begin?

- How often do you notice your symptoms?

- How bad are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, appears to worsen your symptoms?

- Do you have heart disease in your family?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use