Anterior vaginal prolapse (cystocele)

![]() November, 20th, 2024

November, 20th, 2024

Benefit Summary

Anterior prolapse happens when the pelvic floor muscles weaken and the bladder pushes into the top front part of your vagina. Learn how it’s treated.

Overview

, Overview, ,

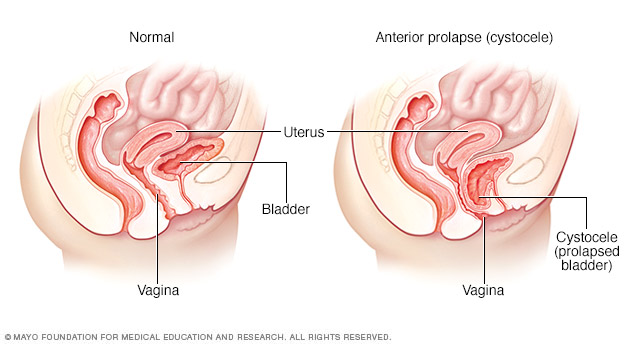

Anterior vaginal prolapse, also known as a cystocele (SIS-toe-seel) or a prolapsed bladder, is when the bladder drops from its usual position in the pelvis and pushes on the wall of the vagina.

The organs of the pelvis — including the bladder, uterus and intestines — are typically held in place by the muscles and connective tissues of the pelvic floor. Anterior prolapse occurs when the pelvic floor becomes weak or if too much pressure is put on the pelvic floor. This can happen over time, during vaginal childbirth or with chronic constipation, violent coughing or heavy lifting.

Anterior prolapse is treatable. For a mild or moderate prolapse, nonsurgical treatment is often effective. In more severe cases, surgery may be necessary to keep the vagina and other pelvic organs in their proper positions.

A dropped or prolapsed bladder (cystocele) occurs when the bladder bulges into the vaginal space. It results when the muscles and tissues that support the bladder give way.

A dropped or prolapsed bladder (cystocele) occurs when the bladder bulges into the vaginal space. It results when the muscles and tissues that support the bladder give way.

Anterior prolapse (cystocele) Symptoms

In mild cases of anterior prolapse, you may not notice any signs or symptoms. When signs and symptoms occur, they may include:

- A feeling of fullness or pressure in your pelvis and vagina

- In some cases, a bulge of tissue in your vagina that you can see or feel

- Increased pelvic pressure when you strain, cough, bear down or lift

- Problems urinating, including difficulty starting a urine stream, the feeling that you haven’t completely emptied your bladder after urinating, feeling a frequent need to urinate or leaking urine (urinary incontinence)

Signs and symptoms often are especially noticeable after standing for long periods of time and may go away when you lie down.

When to see a doctor

A prolapsed bladder can be uncomfortable, but it is rarely painful. It can make emptying your bladder difficult, which may lead to bladder infections. Make an appointment with your health care provider if you have any signs or symptoms that bother you or impact your daily activities.

Causes

Your pelvic floor consists of muscles, ligaments and connective tissues that support your bladder and other pelvic organs. The connections between your pelvic organs and ligaments can weaken over time, or as a result of trauma from childbirth or chronic straining. When this happens, your bladder can slip down lower than usual and bulge into your vagina (anterior prolapse).

Causes of stress to the pelvic floor include:

- Pregnancy and vaginal childbirth

- Being overweight or obese

- Repeated heavy lifting

- Straining with bowel movements

- A chronic cough or bronchitis

Risk factors

These factors may increase your risk of anterior prolapse:

- Pregnancy and childbirth. Women who have had a vaginal or instrument-assisted delivery, multiple pregnancies, or whose infants had a high birth weight have a higher risk of anterior prolapse.

- Aging. Your risk of anterior prolapse increases as you age. This is especially true after menopause, when your body’s production of estrogen — which helps keep the pelvic floor strong — decreases.

- Hysterectomy. Having your uterus removed may contribute to weakness in your pelvic floor, but this is not always the case.

- Genetics. Some women are born with weaker connective tissues, making them more susceptible to anterior prolapse.

- Obesity. Women who are overweight or obese are at higher risk of anterior prolapse.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of anterior prolapse may involve:

- A pelvic exam. You may be examined while lying down and possibly while standing up. During the exam, your provider looks for a tissue bulge into your vagina that indicates pelvic organ prolapse. You’ll likely be asked to bear down as if during a bowel movement to see how much that affects the degree of prolapse. To check the strength of your pelvic floor muscles, you’ll be asked to contract them, as if you’re trying to stop the stream of urine.

- Filling out a questionnaire. You may fill out a form that helps your provider assess your medical history, the degree of your prolapse and how much it affects your quality of life. This information also helps guide treatment decisions.

- Bladder and urine tests. If you have significant prolapse, you might be tested to see how well and completely your bladder empties. Your provider might also run a test on a urine sample to look for signs of a bladder infection, if it seems that you’re retaining more urine in your bladder than is normal after urinating.

Treatment

Treatment depends on whether you have symptoms, how severe your anterior prolapse is and whether you have any related conditions, such as urinary incontinence or more than one type of pelvic organ prolapse.

Mild cases — those with few or no obvious symptoms — typically don’t require treatment. Your provider may recommend a wait-and-see approach, with occasional visits to monitor your prolapse.

If you do have symptoms of anterior prolapse, first line treatment options include:

-

Pelvic floor muscle exercises. These exercises — often called Kegel exercises or Kegels — help strengthen your pelvic floor muscles, so they can better support your bladder and other pelvic organs. Your provider or a physical therapist can give you instructions for how to do these exercises and can help you determine whether you’re doing them correctly.

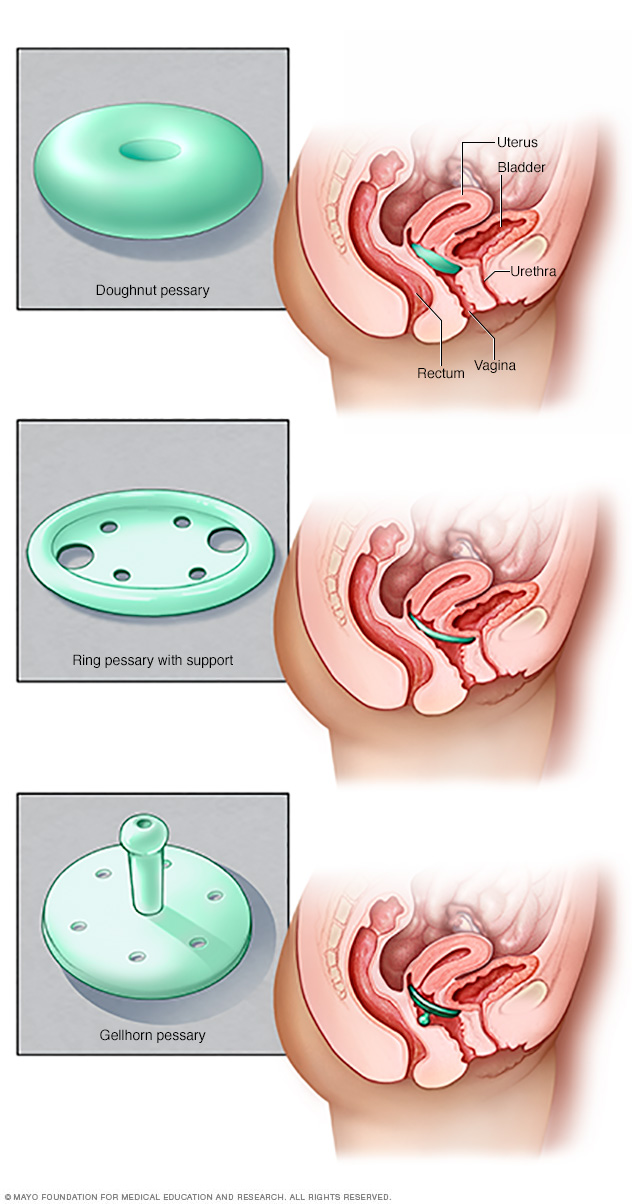

- A supportive device (pessary). A vaginal pessary is a plastic or rubber ring inserted into your vagina to support the bladder. A pessary does not fix or cure the actual prolapse, but the extra support the device provides can help relieve symptoms. Your doctor or other care provider fits you for the device and shows you how to clean and reinsert it on your own. Many women use pessaries as a temporary alternative to surgery, and some use them when surgery is too risky.

Kegel exercises may be most successful at relieving symptoms when the exercises are taught by a physical therapist and reinforced with biofeedback. Biofeedback involves using monitoring devices that help ensure you’re tightening the proper muscles with optimal intensity and length of time. These exercises can help improve your symptoms, but may not decrease the size of the prolapse.

When surgery is necessary

If you still have noticeable, uncomfortable symptoms despite the treatment options above, you may need surgery to fix the prolapse.

- How it’s done. Often, the surgery is performed vaginally and involves lifting the prolapsed bladder back into place using stitches and removing any excess vaginal tissue. Your doctor may use a special type of tissue graft to reinforce vaginal tissues and increase support if your vaginal tissues seem very thin.

- If you have a prolapsed uterus. For anterior prolapse associated with a prolapsed uterus, your doctor may recommend removing the uterus (hysterectomy) in addition to repairing the damaged pelvic floor muscles, ligaments and other tissues.

- If you have incontinence. If your anterior prolapse is accompanied by stress incontinence — leaking urine during strenuous activity — your doctor may also recommend one of a number of procedures to support the urethra (urethral suspension) and ease your incontinence symptoms.

If you’re pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant, you might need to delay surgery until after you’re done having children. Pelvic floor exercises or a pessary may help relieve your symptoms in the meantime. The benefits of surgery can last for many years, but there’s some risk of prolapse happening again — which may mean another surgery at some point.

Pessaries come in many shapes and sizes. The device fits into the vagina and provides support to vaginal tissues displaced by pelvic organ prolapse. A health care provider can fit a pessary and help provide information about which type would work best.

Pessaries come in many shapes and sizes. The device fits into the vagina and provides support to vaginal tissues displaced by pelvic organ prolapse. A health care provider can fit a pessary and help provide information about which type would work best.

Types of pessaries Lifestyle and home remedies

Kegel exercises are exercises you can do at home to strengthen your pelvic floor muscles. A strengthened pelvic floor provides better support for your pelvic organs and relief from symptoms associated with anterior prolapse.

To perform Kegel exercises, follow these steps:

- Tighten (contract) your pelvic floor muscles — the muscles you use to stop urinating.

- Hold the contraction for five seconds, and then relax for five seconds. (If this is too difficult, start by holding for two seconds and relaxing for three seconds.)

- Work up to holding the contraction for 10 seconds at a time.

- Do three sets of 10 repetitions of the exercises each day.

Ask your doctor for instructions on how to properly perform a Kegel, and for feedback on whether you’re using the right muscles. Once you’ve learned the proper method, you can do Kegel exercises discreetly just about anytime, whether you’re sitting at your desk or relaxing on the couch.

To help keep an anterior prolapse from progressing, you can also try these lifestyle modifications:

- Treat and prevent constipation. High-fiber foods can help.

- Avoid heavy lifting, and lift correctly. When lifting, use your legs instead of your waist or back.

- Control coughing. Get treatment for a chronic cough or bronchitis, and don’t smoke.

- Manage your weight. Talk to your doctor to determine your ideal weight and get advice on weight-loss strategies, if you need them.

Preparing for an appointment

Make an appointment with your primary care provider or gynecologist if you have signs or symptoms of anterior prolapse that bother you or interfere with your normal activities.

Here’s some information to help you prepare for your appointment and know what to expect from your provider.

What you can do

- Write down any symptoms you’ve had, and for how long.

- Make note of key medical information, including other conditions for which you’re being treated and the names of medications, vitamins or supplements you regularly take.

- Bring a friend or relative along, if possible. Having someone else there may help you remember important information or provide details on something that you missed during the appointment.

- Write down questions to ask your provider, listing the most important ones first in case time runs short.

For anterior prolapse, some basic questions to ask include:

- What is the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- Are there any other possible causes?

- Do I need any tests to confirm the diagnosis?

- What treatment approach do you recommend?

- If the first treatment doesn’t work, what will you recommend next?

- Am I at risk of complications from this condition?

- What’s the likelihood that the anterior prolapse will recur after treatment?

- Should I follow any activity restrictions?

- What can I do at home to ease my symptoms?

- Should I see a specialist?

Besides the questions you prepare in advance, don’t hesitate to ask other questions during your appointment if you need clarification.

What to expect from your doctor

During your appointment, your provider may ask a number of questions, such as:

- When did you first notice your symptoms?

- Do you have urine leakage?

- Do you have frequent bladder infections?

- Do you have pain or leak urine during intercourse?

- Do you have a chronic or severe cough?

- Do you experience constipation and straining during bowel movements?

- What, if anything, seems to improve your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to worsen your symptoms?

- Does your mother or a sister have any pelvic floor problems?

- Have you delivered a baby vaginally? How many times?

- Do you wish to have children in the future?

- What else concerns you?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. Terms of Use